Mind

“Let’s base all of our choices on whether he likes it or not. This was a radical departure from theater that must entertain hundreds of people in the audience.”

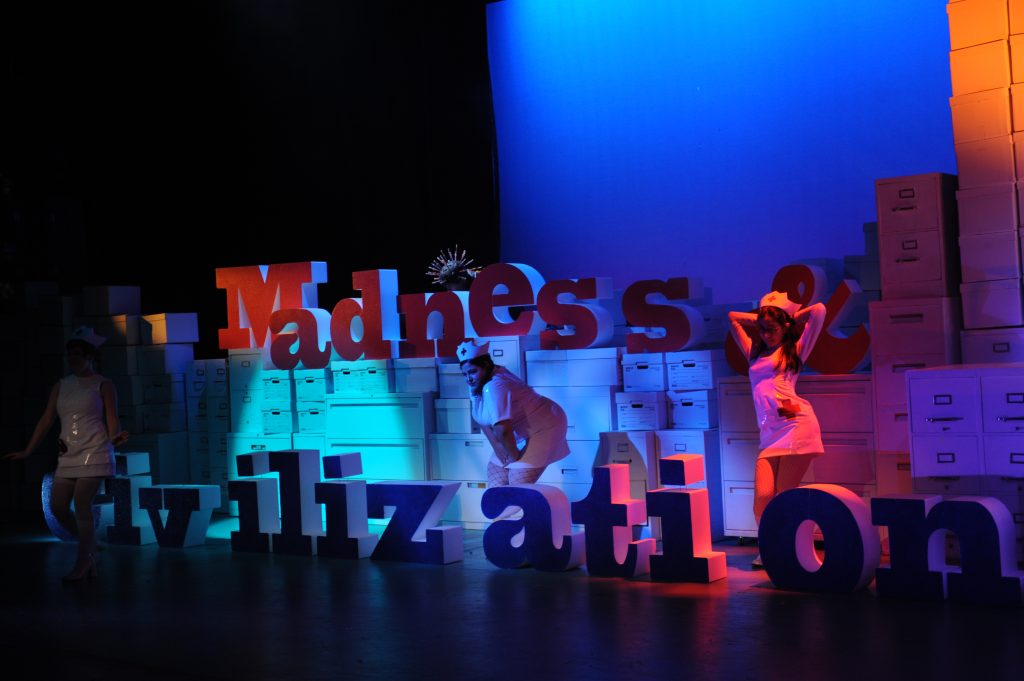

Natsu Onoda Power, a professor in Georgetown’s Department of Performing Arts, was working on an adaptation of Michel Foucault’s Madness and Civilization. Her intended audience was not the typical crowd you might find at a Friday night show or Sunday matinee. It was an audience of one — her brother-in-law who was residing in a group home with others living with mental illnesses.

Onoda Power is known for her ensemble-driven works that bridge visual art and live performance. She’s created visually stunning works out of dense texts like Charles Darwin’s On the Origin of Species and Michael Pollan’s The Omnivore’s Dilemma. But this play was different — a different audience, different site and different purpose.

“The premise was ‘let’s adapt this really historically dense book for this man who’s living with schizophrenia.’ And then the goal is for him to be engaged and entertained throughout.” she says. “Someone who is living with mental illness in a group home is not the ‘intended audience’ for our mainstream media or consumerism; he lives in the margins of society. I wanted to bring him into the center.”

As part of the process, Onoda Power brought the cast and students in her “Performing Madness” class to visit the residents in New Jersey. Like students involved in the adaptation process, students in “Performing Madness” were tasked with exploring representation of mental illnesses in theater and film through performance and reflective exercises.

Onoda Power and the Georgetown students ran an improvisation workshop with the residents, where they found new purpose in familiar rehearsal exercises.

“That turned out to be probably the single most enriching day of my teaching life,” says Onoda Power. “It renewed my understanding of what these theatrical exercises do and what theater does. It is about connecting with another human being.”