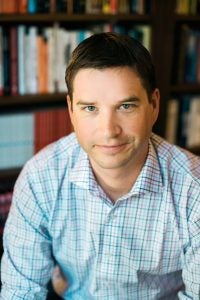

This story is a part of our “Ask a Professor” series, in which Georgetown faculty break down complex issues and use their research to inform trending conversations, from the latest pop culture hits to research breakthroughs and critical global events shaping our world.

Professor Cal Newport doesn’t make New Year’s resolutions. He tunes up his systems and fires up goals at the beginning of the school year.

But the computer science professor does have tips for shaking up the way we work and study in 2024, particularly in the midst of constant distractions, interruptions, pings and dings.

According to new research, people can only focus on one screen for 47 seconds on average, and the brain takes 25 minutes to refocus on a task after a distraction. In constantly diverting our attention to email, chats or newsfeeds while working on something important, Newport says, we exist in a “neurological liminal state of conflicted attention targets.” In other words, we can’t fully focus.

“The true productivity poison in the modern workplace or educational environment are the quick checks of unrelated sources of information that create that persistent state of divided attention,” said Newport, an associate professor in the College of Arts & Sciences and a New York Times bestselling author. “This not only reduces our cognitive capacity but is also exhausting. Both our work and our mental health suffer.”

To evade these distractions, the New Yorker contributor, researcher and podcast host proposes blocking off time to work without any “quick checks.” And in his forthcoming book, Slow Productivity, he proposes a philosophy to produce more meaningful, better quality work in a way that’s sustainable long-term.

“Slow productivity highlights a way forward in which you can sidestep the demands of an always-on hustle culture, and yet still find pride and meaning in your professional efforts,” he said.

The advice can also be applied to students, he says, to avoid burnout and exhaustion and make college more meaningful.

Read on to learn how we got to the state of constant busyness and what you can do to funnel your attention into higher quality work in the classroom and workplace in 2024.