Maureen Corrigan grew up loving all sorts of books. After earning her undergraduate English degree and on her way to her Ph.D., she applied for a job as a book critic at what would become one of the most popular radio shows in America.

She was rejected for being “too academic.” But that didn’t hold her back from trying again.

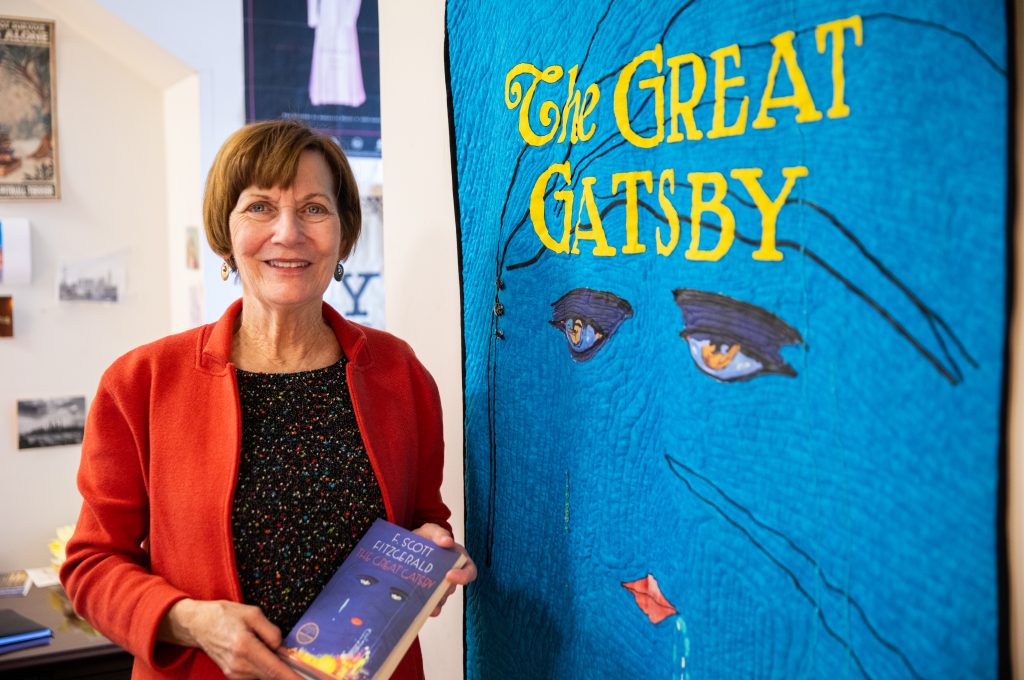

Thirty-five years later, Corrigan is one of the most recognizable radio and podcast voices as the book reviewer for Fresh Air, one of the most popular programs on public radio and a hit NPR podcast.

On top of reading countless books every year for Fresh Air, she also teaches in the College of Arts & Sciences as the Nicky and Jamie Grant Distinguished Professor of the Practice in Literary Criticism. She is also a prolific writer and has authored two books while regularly writing for the Wall Street Journal, Washington Post and other major media outlets

“I still feel like I’ve got the greatest combination of jobs in the world,” Corrigan said. “I get to go back and read classics like The Great Gatsby every year with my students, and then I get to read the latest books that are coming down the pike.”

Discover how Corrigan found her love of books and became one of the country’s most popular book critics.

Behind the CV: Maureen Corrigan on NPR, Book Reviews, and What Makes a Great Read

My love of reading came: early from my dad, who was a refrigeration mechanic and loved to read. He would come home from work installing refrigeration systems on buildings all over New York City and he would always crack open a paperback, usually an adventure story about World War II since he had been in the war, but also detective novels and some canonical novels. I remember one day when he saw me reading A Tale of Two Cities for school and he said, “That’s a good one.” So that kind of encouragement to read really took root.

The first book that made me upset: was Mrs. Wiggs of the Cabbage Patch because my mother was set on giving it to a younger cousin and I wanted to keep that book. I was probably around six and I really loved that book because it was about a woman with a lot of children. As an only child I was fascinated by big families.

The summer of 1975 was magical because: One of my wonderful English professors at Fordham, Mary Fitzgerald, took six of us rabid English majors to the Yeats International Summer School. She knew Seamus Heaney, who later won the Nobel Prize, and we kept running into him all throughout that trip in Dublin and Sligo. My memory of that summer is of a time that was enchanted. I met a lot of writers and poets and saw that they were living a life immersed in literature, and I felt that somehow such a life might be possible.

Why I hated my Ph.D program: I went to Fordham University for college and had the greatest professors of my life there, and they inspired me to go ahead for my Ph.D. I was fortunate to be awarded a fellowship to the University of Pennsylvania, but hated the Ph.D program — although I stuck it out because I wanted to be a professor. I was at Penn during the period when deconstruction and continental critical theory ruled, and I found those ways of talking about books deadening and, now I would say, elitist, too.

I love to teach because: It’s a lot like opening up a fresh book. You walk into the classroom the first day of the semester, and you don’t know who you’re going to be with for the next few months and what your shared experience is going to be. When a class gels, you really feel, as a professor, that you and your students are all together on a freshly illuminating and, sometimes, unpredictable journey through the material.

I got into reviewing books when: a friend of mine in graduate school asked if I would help her with a take-home editing test for a job she was applying to at the Village Voice, which was back then the greatest alternative newspaper in America. The Village Voice is the newspaper that the Georgetown Voice is named after. I helped her, and as a way of thanking me, she asked if I wanted to try to write a book review for the literary supplement. Writing that review felt like the magic antidote to what I so disliked about academic writing. It was as if somebody gave me a life support system to get through the rest of graduate school. In my reviews I could write about books with enthusiasm and humor and, I hope, intelligence, rather than putting my voice through what I considered to be the “deflavorizing machine” of academic critical theory.

After getting my job on Fresh Air I felt:

After getting my job on Fresh Air I felt: