With over 16,000 members in its religious community around the world and 28 colleges and universities and dozens of high schools and primary schools in the United States, the Jesuits make up the largest male religious order in the Catholic Church and have left a significant imprint on American education.

But how did the Jesuits establish themselves as a major influence in American Catholicism and become known for their schools such as Georgetown?

A new book by Rev. David Collins, S.J., an associate professor in the College of Arts & Sciences, explores the history of the Society of Jesus in the U.S. from the early colonial period through the modern era. In The Jesuits in the United States: A Concise History, published by Georgetown University Press, Collins traces the roots of his religious order and how Jesuits shaped — and were shaped by — Catholicism in the U.S. and the broader American society.

Read on to learn how Jesuits established such a significant presence nationwide, how the order became a mainstay in American education and the challenges the Society of Jesus faces in the 21st century.

David Collins, S.J., on Jesuits in America, Catholic History and the Future of the Society of Jesus

How did the Jesuits first arrive in the Americas and get a foothold in what would become the United States?

The Jesuits piggybacked on each of the colonial ventures into the Americas, following the Spanish into South and Central America, the French into northern North America, and the English into a small part of the 13 colonies. The distinctive part of the English colonies was that the English empire was specifically Protestant. That meant English Catholics were living underground in England or in exile in continental Europe in the early 17th century.

The Maryland colony became a fascinating exception. The colony’s founding family, the Calverts, were in fact Catholics. The Calverts made a very careful set of implicit agreements with the English kings that as long as the Church was not established in any form and the Catholics were discreet, then they could legally practice their religion in Maryland. The Calverts then recruited Jesuits to come with them to Maryland, two priests and a lay brother, whose names will be familiar to Hoyas on account of building names on campus: Andrew White, John Gravenor and Thomas Gervase.

That religious liberty in Maryland at its founding was unique. Catholics were not welcome anywhere else in the 13 colonies.

You write that the Jesuit focus on education in the U.S. is particularly distinctive. How did the Jesuits leave such a significant footprint in the American education system?

The Jesuits realized early on in their history that schooling is such a contribution to Christian life and to the common good.

In the colonial period, there was a real gap in the education system in Europe. You had grammar schools and universities, but little in between, especially for lay people. That’s where the Jesuits jumped in. First in Europe, then around the world and in Maryland, Jesuits arrived and founded schools.

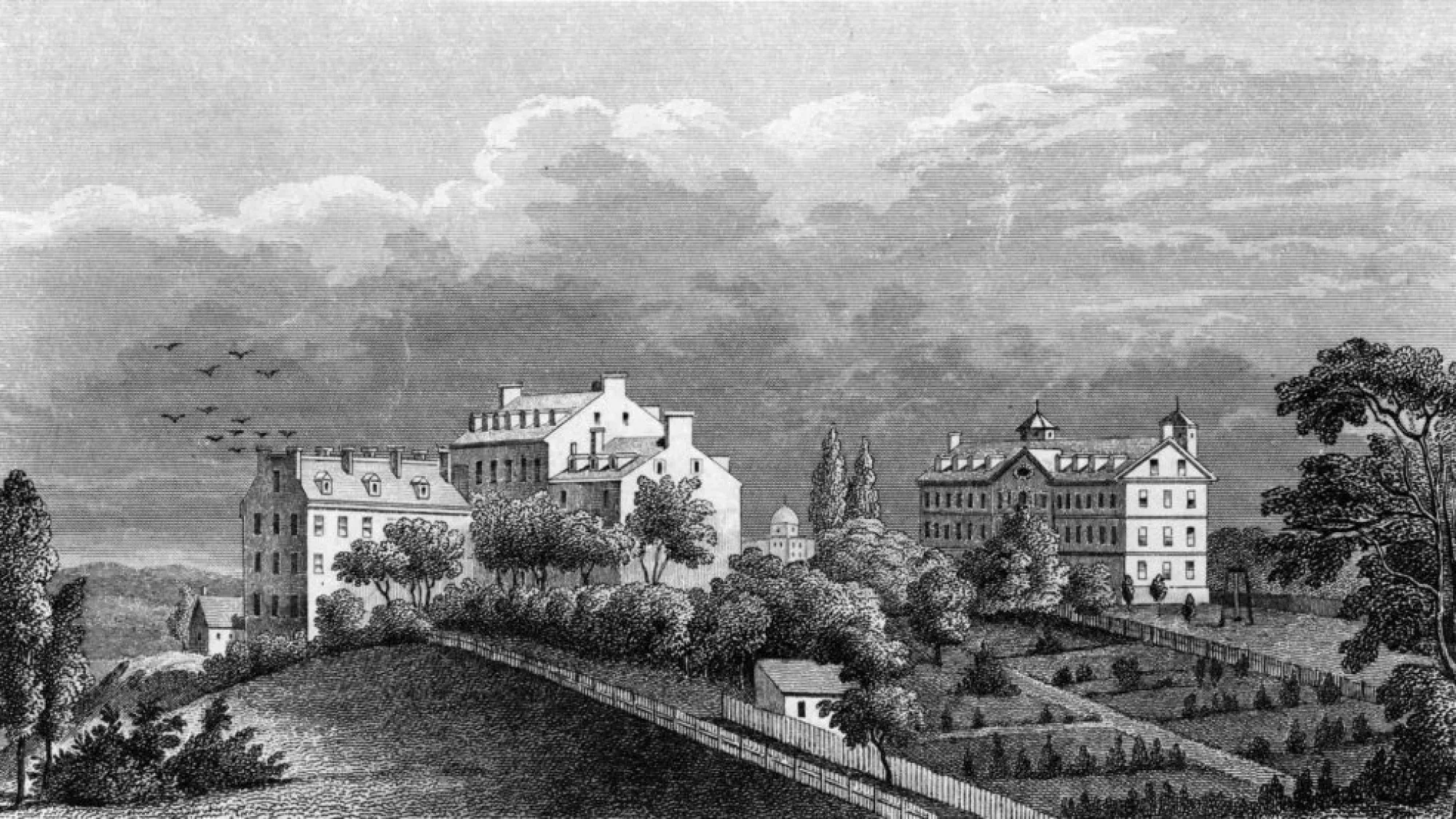

Their early successes in Maryland were quite limited, but they were determined. Still, it was not until John Carroll became the first Catholic bishop in the U.S. that that original Jesuit vision was realized in 1789 in Georgetown. It was part of a larger program to build up the Catholic Church in the U.S., and his large vision included founding parishes up and down the East Coast, establishing a seminary and working toward schooling for women.

In addition to tapping that older tradition of wanting to have a college, he also saw the college as an important tool in cultivating vocations to the priesthood and making education available to Catholic families for whom sending their sons to Europe was too expensive or inconvenient. Thus, Georgetown was founded.

How were Jesuit schools such as Georgetown distinct from other educational institutions in the early United States?

The early colleges in other colonies were not open to Catholic students. Carroll should be admired for not including a religious test for students at Georgetown. There was a principle at stake: Catholics had benefited uniquely in Maryland from the idea of religious toleration. Carroll was committed to extending to his fellow countrymen the ideas that he and his fellow Catholics had benefited from.

How did you approach the topic of Jesuit slaveholding in your book?

I’ve been confronted by this history for as long as I’ve been a Jesuit. When I was a novice in the 1980s, a senior Jesuit historian introduced us to the history of the Maryland Jesuits, including their history of slaveholding. We were all stunned. I’ve been hardwired both by my training as a Jesuit and a historian to pursue the whole history, good and bad, rather than cherry-picking the happy parts and turning a blind eye to the sad parts.

My goal in this concise history has been to put the slaveholding in its context. That means looking at the slaveholding that was lamentably common for Jesuit missionaries around the globe and at plantations across the U.S.: In the mid-18th century, the 200 or so people enslaved by Maryland Jesuits were among about 21,000 people enslaved by Jesuits globally. And the roughly 300 enslaved people sold by the Maryland Jesuits to Louisiana businessmen in the 1830s were among 1 million enslaved people forcibly sent by plantation owners from the Upper South to the Deep South in the early 19th century.

How did Jesuits shape Catholicism in the U.S. and its relationship with the broader American society?

American Jesuits have consistently tried to keep Catholicism engaged with mainstream American society. Part of this goes back to the religious freedom of the Maryland colony, but it extends to the present in the Jesuit commitment to, for example, the modern research university, which is itself a very “secular” place, but a place where the Church benefits from being a part of and to which the Church has important things to contribute.

Throughout this history, Jesuits have striven to make American Catholics full beneficiaries of American society’s resources and to make Catholic resources and insights shapers of that same American mainstream.

That’s not the only way of being Catholic. One could also imagine a different goal of segregating one’s own community to keep it safe from outside influences, which can also lead to flourishing as exemplified by the Amish. Jesuits have never operated much in that self-segregating way. And that’s made an important overall contribution in the history of Catholicism in the U.S.

You describe the most recent period of Jesuit history as a period of upheaval. What’s the primary challenge facing American Jesuits today?

There’s a phrase that comes from an older Jesuit that the Jesuits exist to explain the Church to the world and the world to the Church. Jesuits think of themselves as uniquely situated to be intermediaries in modern culture.

We know we’re facing a challenge today that has to do with the unchurching of America, the rise of the nones who affiliate with no religion. Since so many of us work on campuses, we’re on the frontlines of the challenge.

Young people today, even when they identify as Catholic, often come from minimally churched backgrounds. The struggle is figuring out what’s the best way to draw them back into the Church. Every generation has its struggle. This is the one that we’re in the midst of.

How do you see your role as a Jesuit priest in responding to that challenge and serving the overarching mission of the Society of Jesus in the U.S. today?

I like to think of myself as taking the best of what is consistent in our tradition and applying it to the needs that are particular to the present moment.

When I walk into a classroom or any meeting on a university campus, I’m at the cutting edge of the kinds of challenges that the Church is facing with a population that is disillusioned with authority and thinks that the Church needs to be knocked down a peg or two.

That’s the challenge that gets me out of bed every day. The classroom is in many respects mission territory. What’s the difference between me stepping into a classroom today and Andrew White stepping into the wilds of the Maryland forests for the first time in 1634? It might be a little grandiose, but it gives me a vision. Rare is the day that I don’t leave the classroom even more energized by these challenges than when I entered it. First-rate students, of course, deserve the credit for that.

Where do you see the Jesuit order going in the U.S. in the next 50 years?

The Jesuits are always looking to capitalize on their best advantages, not so that Jesuits are always in the headlines, but so that broader elements of the Church are engaged with important contemporary problems all for the sake of the greater glory of God and the common good.

Things come and go. The Jesuits don’t have to exist 50 years from now, but I’m fairly convinced that they will because they have these tools that have been so successfully applied again and again across 500 years.