Key Findings

- Many young athletes who experience repetitive mild head impacts may develop symptoms commonly associated with chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE) but don’t actually have CTE.

- Isolated mild head impacts do not appear to cause permanent brain damage.

- Repetitive mild head impacts may cause the brain to turn off key receptors that can lead to chronic symptoms associated with neurodegenerative disease.

- Current research examines how treatments could help patients before they receive multiple head impacts or reduce symptoms after head impacts

Concussions are one of the most common injuries related to youth sports.

Repetitive head impacts over time can lead to neurodegenerative disease like chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE), which can spur memory loss, aggression, self-harm and other symptoms.

Today, many young athletes who experience repetitive head impacts can exhibit symptoms of neurodegenerative diseases like CTE, which has no cure. However, they don’t always have CTE, said Mark Burns, professor of neuroscience at the School of Medicine.

At Georgetown, Burns studies what happens in the brain when someone experiences head trauma. He’s also working to develop possible treatments for people who exhibit symptoms of neurodegenerative disease after repetitive head impacts.

“There’s a lot of press about young athletes exhibiting abnormal behavior after repeat concussions. We are trying to understand what symptoms are associated with early-stage CTE that might be reversible, and what symptoms are associated with late-stage CTE that may not be reversible,” Burns said. “We’re trying to reverse those symptoms that are associated with early-stage CTE and give people hope.”

How Traumatic Brain Injury Changes the Brain

Brain injury occurs as a spectrum that encompasses mild head impact all the way up to severe traumatic brain injury (TBI). When you suffer from a TBI, the brain undergoes massive changes.

Nerve cells in the brain die, including the neurons, axons and synapses that transmit messages through the entire body. The head impact also creates inflammation in the brain that remains for decades, Burns said.

“A moderate-to-severe TBI is a life-changing event. You are not going to be the same afterward,” Burns said. “It’s going to be a big recovery. There are no treatments. All we can do is clinically manage the symptoms and rehabilitate the person.”

TBI can also lead to neurodegenerative disease. Studies that looked at people with a TBI showed that the brain can develop amyloid plaques within hours of injury, Burns said.

These amyloid plaques, or accumulations of protein in the brain, are the same type of substance that everyone develops typically starting in their mid 50s, Burns said. They’re also the hallmark of patients with Alzheimer’s disease, who accumulate these proteins at a far higher rate than the average person.

Previous studies have shown that severe TBI increases the risk of dementia five times, while a moderate TBI doubles the risk for dementia, Burns said.

“The amyloid in the brain that usually takes 60 to 80 years to accumulate in a normal lifespan was suddenly being found in 10-year-old children and 25-year-old people who had been in car crashes,” he said. “That was the first mechanistic indication that something was happening acutely after brain injury that might be triggering these long-term neurodegenerative processes.”

The Effects of Repetitive Mild Head Impacts

While Burns studies moderate-to-severe head impacts, he is also interested in the effects of milder head impacts. These types of contact include what a high school football player might encounter during a tackle or when a soccer player headbutts a ball.

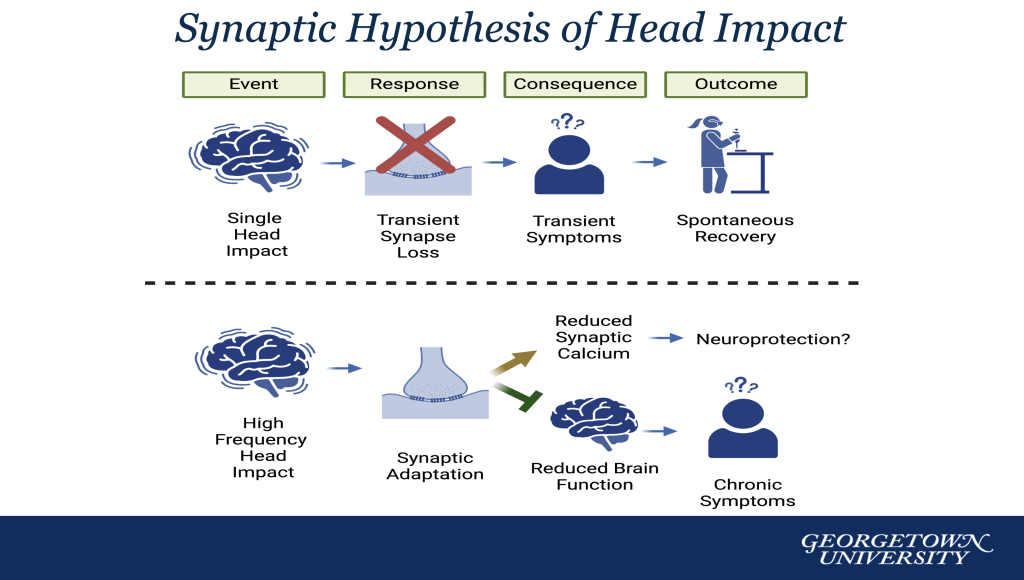

His research has shown that mild impacts — isolated incidents like concussions, where patients recover within a couple of weeks — do not appear to cause any permanent damage

“For most of those single [mild] head impacts, nothing dies. No inflammation happens. We don’t get cell death. We don’t break axons,” he said.

But Burns did want to find out why people like athletes who receive concussions seem to exhibit signs of neurodegeneration.

His team discovered that repeated mild head impacts over a short period of time can cause neurodegenerative symptoms.

In a normal brain, a neuron’s synapses release neurotransmitters to receptors in other neurons to communicate. When the brain experiences a head impact, neurons release even more neurotransmitters that reach more distant receptors. When these distant receptors are activated too often, it can cause excitotoxicity — a process in which overstimulated neurons die, Burns said.

Repetitive head impacts can cause the brain to change its receptors in the synapse, possibly as a defense mechanism, Burns said. The reduction of receptors means that the brain isn’t functioning normally and can cause chronic symptoms, including reduced memory and increased risk-taking behaviors.

“The brain is rewiring. The synapses are restructuring,” he said. “We think the brain is trying to protect itself. The brain is detecting the minor head impacts, and it thinks a bigger head impact may occur in the future, so it changes the receptors on its synapses and essentially turns the brain down by about 30% in a protective manner.”

The reason the brain does this is unknown, Burns said, and his lab is working to figure it out. In the meantime, Burns wants athletes who might suffer from neurodegenerative symptoms to have hope that treatment may exist in the near future.

“The message we want to get out is that this is a physiological event and not a pathological event,” Burns said. “Pathological in terms of neurodegenerative disease is untreatable. Physiological means something has happened in the way your brain and body are working. That means what I’m describing is treatable.”

Potential Treatments for Patients With Multiple Head Impacts

Burns is also investigating a possible treatment that could block the onset of neurodegenerative symptoms.

His lab is experimenting with a drug typically used to treat the symptoms of patients with Alzheimer’s disease to prevent the loss of brain tissue.

The drug turns off the more distant receptors in the synapse. Burns is studying whether athletes could benefit from the drug as a preventative measure by temporarily turning off the more distant receptors in the synapse before they receive multiple head impacts. His current research shows promise that the drug successfully turns off these receptors and can prevent the synapse changes and cognitive deficits usually caused by repeated head impact.

Burns is also researching a possible treatment for people who have already received multiple head impacts and have exhibited some symptoms of neurodegeneration.

His lab is studying whether low-level electrical currents could reactivate the parts of the brain that are turned down when the brain tries to protect itself after multiple mild head impacts.

“What we’re trying to do is give doctors the tools that can help reverse these symptoms,” Burns said. “Once an athlete has stopped playing sports, and if they have these symptoms, how can we bring back their full brain potential so that they don’t have these symptoms anymore?”

For Burns, his research comes with urgency as suicide is often correlated with people who have CTE or think they have the incurable disease.

In a 2023 study from Boston University, scientists studied the brains of 152 young athletes who had experienced numerous head impacts playing contact sports and died by suicide. The research showed that 41% of the subjects suffered from CTE.

Burns hopes his research will lead to new treatments and shed more light on the 59% of athletes who exhibited symptoms but did not have CTE.

Sports play an important role in children’s lives, Burns said, and he wants his research to help families make informed decisions — and reassure athletes that experiencing symptoms does not necessarily mean they have an untreatable disease.

“There has been a lot of fear of head impacts in the last 20 years. While it’s warranted, I’m concerned it’s driving people away from sports,” he said. “If you have a child who is crazy about playing sports, and that’s the only reason they go to school, then you don’t want to take that away from them. It’s our job to give athletes as much information as we can about what’s happening when they’re exposed to head impacts, and it’s our job to try and come up with treatments for them.”